Flicker Alley is proud to present the following essay by John Grant/Noirish, written for Detectives and Dames: A Flicker Alley Noir Blog-a-Thon! Too Late for Tears (1949) is available NOW on Blu-ray/DVD! Order today!

John Grant is an award-winning writer and author of A Comprehensive Encyclopedia of Film Noir. His website is at www.johngrantpaulbarnett.com.

Note: This essay contains spoilers for Too Late for Tears. The screen captures below were taken directly from Flicker Alley’s DVD version of the film.

vt Killer Bait

US / 102 minutes / bw / Hunt Stromberg, UA Dir: Byron Haskin Pr: Hunt Stromberg Scr: Roy Huggins Story: Too Late for Tears (1947, originally serialized in Saturday Evening Post) by Roy Huggins Cine: William Mellor Cast: Lizabeth Scott, Don DeFore, Dan Duryea, Arthur Kennedy, Kristine Miller, Barry Kelley, Smoki Whitfield, David Clarke, Billy Halop.

If there was any single movie or actor that set me off on the long and winding course toward writing A Comprehensive Encyclopedia of Film Noir, Too Late for Tears was that movie and Lizabeth Scott was that actor.

If there was any single movie or actor that set me off on the long and winding course toward writing A Comprehensive Encyclopedia of Film Noir, Too Late for Tears was that movie and Lizabeth Scott was that actor.

I first watched the movie sometime in the early 2000s. Before that I’d written quite extensively on animation—in fact, I’d not so very long before seen publication of my book Masters of Animation—and on fantasy movies, for The Encyclopedia of Fantasy, edited by John Clute and myself. I’d been playing around with various ideas for more books on animation and/or the cinema of the fantastic, but then, for some reason—perhaps just because it came on TCM while I was sitting on the couch, who knows?—I found myself watching Too Late for Tears for the first time.

And it felt like coming home.

Of course, I’d watched countless films noir before then, and liked them a lot—The Blue Dahlia (1946) was a particular favorite (have I ever mentioned my longtime crush on Veronica Lake?)—but Too Late for Tears really jolted me: it was my gateway into a new passion. In the first place, it was an impeccably told tale that moved with pace and vigor. Second, there’s only a single really likeable character in the movie, and she’s one of the secondary cast; as someone who’s often written antiheroes myself, I couldn’t help but be captivated by this.

And third, and most particularly—pace Barbara Stanwyck’s Phyllis Dietrichson in Double Indemnity (1944), Jane Greer’s Kathie Moffat in Out of the Past (1947), Bette Davis’s Leslie Crosbie in The Letter (1940), Linda Fiorentino’s Bridget Gregory in The Last Seduction (1994) and all the other usual suspects—the movie had what I regard as the most splendid femme fatale in all of film noir: Lizabeth Scott’s Jane Palmer.

Jane Palmer is a woman entirely consumed by greed. She’s a murderess. She uses her sex if she has to in order to get what she wants. She seems to have no conception of the warmer human emotions like love and affection; the death of her husband affects her little if at all. And yet, thanks to Scott’s portrayal of her, she projects a considerable allure. By the end of the movie, despite all the dreadful crimes and betrayals we know she’s committed, there’s still a part of us that’s on her side.

So that’s when my viewing tastes began their very radical shift—one that didn’t thrill my wife too much, to be honest. An expert on animation art, she’d become devoted also to fantasy and sf movies because of my enthusiasm for them, and now here I was suddenly deserting her, as it were, for all kinds of depressing old black-and-white outings, often in murky prints.

One of the drawbacks of running Noirish is that I’m so busy watching stuff that for the right or wrong reasons didn’t get into A Comprehensive Encyclopedia of Film Noir that I rarely get the opportunity to revisit old noir favorites. When the folks at Flicker Alley approached me to tell me they were planning the release of a new restoration of this movie (and of Woman on the Run [1950], another noir movie that I rate highly) and asked me to take part in their associated blog-a-thon, I leapt at the excuse to watch Too Late for Tears again for the first time in some years.

Jane Palmer (Scott) and husband Alan (Arthur Kennedy) live in Hollywood. One night they’re out driving through the canyons when someone hurls a bag containing $60,000 into the back of their car. When they get home, Alan’s insistent they should turn the money over to the cops; Jane’s equally insistent they should accept it as a lucky windfall. Eventually they compromise and deposit it in Union Station’s baggage department with the aim of fetching it out again in a week’s time, by when they’ll have decided what to do.

Jane has, of course, already made that decision—we knew that by the expression on her face when she and Alan first opened the bag and discovered its contents.

She starts buying herself some pricey frivolities, hiding them in a cabinet beside the kitchen sink. (Husbands never have reason to look inside kitchen cabinets, do they?) That’s where they’re found by blackmailer Danny Fuller (Dan Duryea) when—having traced the Palmers through their car’s license plate—he comes barging into the apartment demanding the payoff loot that was intended for him. As soon as he sees Jane’s covert luxuries he knows for certain she’s been lying about the money.

Jane reckons the only thing to do is play along for time.

Danny: “Stalling, honey?”

Jane: “What do I call you besides Stupid?”

Meanwhile Alan, too, discovers about her spending—the canceled checks from the bank are a bit of a giveaway—and is a tad on the miffed side:

Alan: “Jane, Jane, what’s happening to us? What’s happening? The money sits down there in an old leather bag and yet it’s tearing us apart. It’s poison, Jane. It’s changing you. It’s changing both of us.”

Jane: “I wish it were that simple, Alan. But I haven’t changed. It’s the way I am.”

Jane filches Alan’s old service revolver and sets off with him for a rendezvous with Danny, her plan being to murder Alan and rope in Danny to help dispose of the body. On the way, she has second thoughts and tries to back out, but then Alan discovers the gun, they struggle, the gun goes off and, in traditional noirish fashion, Alan’s a goner.

As per plan, Jane enlists Danny as her accomplice in getting rid of the body and covering up what’s happened. She thereby completely ensnares him in her web.

Jane sets up a clumsy charade to try to persuade Alan’s unwed sister Kathy (Kristine Miller), who lives in the apartment across the hall, that Alan may have absconded, perhaps with another woman—and even phones the cops to report him missing. But Kathy, who idolizes her brother and instinctively distrusts Jane, is having none of it. When Jane’s out, she searches the apartment; she finds Alan’s service gun missing and also notices the Union Station claim ticket.

The conspirators (Lizabeth Scott, Dan Duryea) advance their scheme.

The conspirators (Lizabeth Scott, Dan Duryea) advance their scheme.

Just to add to Jane’s problems, a newcomer arrives on the scene, saying he’s a wartime Air Force buddy of Alan’s, Don Blake (Don DeFore), who thought he’d use part of his ten-day furlough in town to look up his pal and chew the fat about the good old days. DeFore plays the role as one of those people whose outer persona is that of a friend to all the world, one of the really good, open-hearted guys, but who’s actually a complete shit. So, just as Kathy is instinctively distrusting Jane, we’re instinctively distrusting Don, who seems quite obviously a phony in some way.

Meantime Kathy, ignoring what we see, starts falling in love with him—and doesn’t lose faith in him even after Jane hauls in a genuine old USAF comrade of Alan’s, Jack Sharber (David Clarke), to prove Don never served alongside Alan…

There are plenty of further revelations along the way to the movie’s high-powered finale. Don is really Don Blanchard, brother of Jane’s first husband; he suspects his brother didn’t kill himself, as the official story has it, and is here to do some digging. Alan, we discover, distrusted Jane as much as Kathy does, and took measures to make sure she couldn’t check the money out at Union Station. Even so, in the end Jane does get away with the dough, but that’s far from the end of the story.

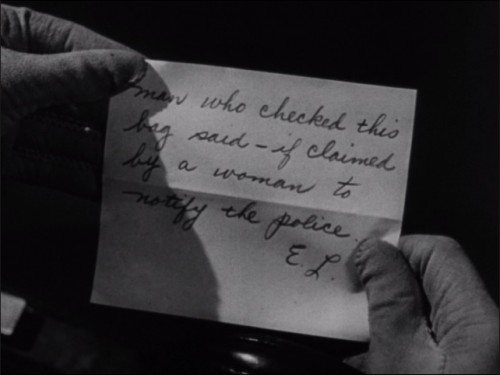

Alan’s note on the bag at Union Station has two possible readings.

Alan’s note on the bag at Union Station has two possible readings.

There are all sorts of clever little plotting tricks, too. When Alan has first deposited the money at Union Station, there’s some play made with the fact that the claim ticket has gone through the hole in his coat pocket into the lining. It doesn’t seem important at the time, but it’ll later give Jane a nasty surprise—and us an enjoyable one. There’s a bit of business with Alan’s gun that really should have persuaded Kathy of Jane’s integrity but in fact persuades her of exactly the opposite. There are so many of these little moments of intrigue in the plot that we learn never to take anything about the movie for granted.

Scott’s clearly the unchallenged star of Too Late for Tears, but she’s ably backed up by Duryea, who here plays precisely the sort of sleazebag that he almost patented during this period of film noir. Even so, soon after meeting Jane, Danny, sleazebag or no, realizes he’s out of his depth when it comes to corruption of the soul. He habitually calls her Tiger, initially in a rather patronizing way but soon with a definite sense of wariness.

The other striking performance comes from Miller as Alan’s sister Kathy. Miller shared some history with Scott. Both of them went to Warner Bros in 1944 for screen tests, and both of them were given the thumbs-down by Jack Warner. However, producer Hal Wallis thought otherwise, and when he moved to Paramount he contracted the two actresses. Miller’s screen debut came in 1945 with You Came Along, in which she had a bit part (under her real name, Jacqueleen Eskeson) while Scott, also debuting, headlined with Robert Cummings. (Next on the cast list was Don DeFore, similarly placed in Too Late for Tears.) Although Miller didn’t become the noir icon that Scott did, they appeared together in several noir or noirish movies: Desert Fury (1947), I Walk Alone (1948) and Paid in Full (1950). (The two former are in the encyclopedia; I’m hoping to discuss Paid in Full on Noirish in the not too distant future.)

Scripter Roy Huggins, who based Too Late for Tears on his own serial novel of the same title, was one of those who radically altered the landscape for screenwriters. He first entered the movies when contracted by Columbia to adapt his novel The Double Take (1946) for the screen as I Love Trouble (1948). He worked as a scripter at Columbia for a while before moving in 1955 to Warner Bros’ TV division. There he created such legendary shows as Maverick (1957–62) and 77 Sunset Strip (1958–64). But Jack Warner used devious means to swindle Huggins out of the creator rights and residuals in those shows, with the result that Huggins left Warner and became far tougher about his rights. When United Artists bought The Fugitive (1963–7), Huggins was paid not just creator residuals but also a full producer’s fee, even though UA gave the production to Quinn Martin. Such an arrangement was written into all Huggins’s further contracts, and other creators began successfully to emulate his aggressive approach. Later he co-created (with Stephen J. Cannell) The Rockford Files (1974–80), a PI show that shared James Garner as its star with the movie Marlowe (1969); it’s been commonly observed that Jim Rockford is very much like Garner’s portrayal of Raymond Chandler’s rumpled hero Philip Marlowe.

Scott’s performance in Too Late for Tears is really quite spectacular, as you’ll have gathered. There’s often been a tendency to dismiss her as a sort of cut-rate Lauren Bacall but here she demonstrates that, while Bacall most undoubtedly had her own unique screen fascination, Scott was arguably the stronger of the two actresses. Her contribution to noir can be gauged by the movies she made in the genre:

- The Strange Love of Martha Ivers (1946), dir. Lewis Milestone

- Dead Reckoning (1947), dir. John Cromwell

- Desert Fury (1947), dir. Lewis Allen

- I Walk Alone (1948), dir. Byron Haskin

- Pitfall (1948), dir. André De Toth

- Dark City (1950), dir. William Dieterle

- The Company She Keeps (1951), dir. John Cromwell

- The Racket (1951), dir. John Cromwell

- Two of a Kind (1951), dir. Henry Levin

- Stolen Face (1952), dir. Terence Fisher

- The Weapon (1956), dir. Val Guest

It’s an impressive collection. I recently rewatched the last of these, the London-set The Weapon, on the grounds that I hadn’t hugely enjoyed it the first time around. I completely reappraised my opinion on the second viewing. Scott plays the widowed mother of a small boy, Eric (Jon Whiteley), who, after accidentally shooting a friend with a gun he’s found while playing on an old bombsite, goes on the run. A Scotland Yard detective (Herbert Marshall) and a tightass US military cop (Steve Cochran) join the hunt for the boy because the gun in question was used in a murder eight years ago. A smooth-talking stranger (George Cole) moves in on Scott’s character, ostensibly to help her find her son and romance her but in fact (this isn’t kept a secret from the audience) to recover the gun because, yes, he was that long-ago murderer.

Scott’s magnificient as the harried mother—a long way away from her femme fatale roles—and the movie’s distinguished also by the presence of young Jon Whiteley; here he has a part not unlike the one he had in the tremendous Dirk Bogarde vehicle Hunted (1952; vt The Stranger in Between), but is unfortunately given rather less to do beyond a lot of very determined-looking running away. This highly talented child actor appeared in just five movies plus an episode of The Adventures of Robin Hood before his mother insisted he end his cinema career to focus on his education. For his performance in The Kidnappers (1953; vt The Little Kidnappers) he shared with costar Vincent Winter a Junior Academy Award. In later life he became an art historian, working at the Ashmolean, Oxford, and publishing several books.

At the time she made The Weapon, Scott was essentially in flight from Hollywood.

With the help of an ex-Communist, now staunchly McCarthyist, editor called Howard Rushmore, the publisher Robert Harrison issued a monthly scandal sheet called Confidential (launched 1952). The m.o. of Confidential was to send the prominent people involved in any news story, true or invented, a copy of that story plus an offer to let the individual “buy back” the story—in other words, the operation was a hairsbreadth away, if that, from being an extortion racket. When in 1955 Rushmore prepared a story to the effect that Scott was a highly promiscuous near-call girl and “baritone babe”—i.e., lesbian—and sent it to her, she refused to cough up but instead had the guts to very publicly sue the rag. Thanks to the incompetence of the U.S. judicial system, the suit eventually, in 1957, collapsed. (Hollywood struck back with the movie Slander [1957], dir. Roy Rowland, in which muckraker Steve Cochran persecutes TV puppeteer Van Johnson with eventually fatal results.)

The year 1957 saw Scott costar in an Elvis Presley movie, Loving You, dir. Hal Kanter (her singing voice was dubbed), but the rumors about her sexuality refused to die and she effectively ended her involvement with the cinema, focusing instead on a brief career as a singer; her jazz-oriented album Lizabeth (1958) can be found today on YouTube, and, while hardly a world-shaker, is well worth a listen.

As an actress, she made fewer than a handful of TV appearances in the 1960s before being lured back to the big screen for one final time in Mike Hodges’ determinedly unfunny comedy Pulp (1972), a Michael Caine vehicle that clumsily homages noir and hardboiled fiction. Scott can’t save it, and neither can various other noirish stalwarts: Mickey Rooney, Lionel Stander and Al Lettieri.

It’s been theorized that it wasn’t really the Confidential faux-scandal and the subsequent failed lawsuit that doomed Scott’s screen career, that her career was anyway in decline and was dealt its deathblow when all sorts of movie actors returned from service in World War II and, resuming their rightful places in Hollywood’s pantheon, ousted those lesser stars who’d filled in during their absence. I don’t buy this theory. For one thing, I can’t think of a whole lot of female Hollywood stars who were absent on active service during World War II…

When I read in late January 2015 that Lizabeth Scott had died, I let out a cheer—not because she had died but because, having reached the grand old age of 92, she had outlived small-minded detractors like Howard Rushmore and Robert Harrison and their readers—and all the others who thought her sexual orientation was of any importance or had any relevance to her acting skills. I haven’t the first idea if Scott was bisexual (she certainly had plenty of heterosexual liaisons) and frankly I couldn’t care less. The issue seems strangely unimportant when set alongside her screen performances.

For me, the voyage of discovering the great actress Lizabeth Scott began with Too Late for Tears. For you, it may have begun somewhere else. Whatever the case, I can’t imagine your voyage has been a less than rewarding one.