Stan Brakhage had a voracious appetite for visionary experience in all forms. Not only did Brakhage pursue a radical approach to filmmaking between 1953 and 2003, he also lectured widely and wrote on the history of cinema, art, literature and aesthetics, and maintained a substantial collection of artist-made and classic films for home viewing. In equal measure, Brakhage saw and re-saw most of the films featured in the Masterworks of American Avant-garde Experimental Film 1920-1970 Blu-ray/DVD retrospective and engaged in dialogues with many of the filmmakers. Thus Brakhage’s personal encounters and writings directly influenced overlapping generations of active practitioners, including Ralph Steiner, Joseph Cornell, Maya Deren, Marie Menken, Kenneth Anger, James Broughton, Ian Hugo, Lawrence Jordan, Jim Davis, Bruce Baillie, Jonas Mekas, Amy Greenfield and Phil Solomon. The extended conversations, whether between artists or among artists and films, nurtured a vibrant art forum in America.

In honor of the Blu-ray/DVD release of Masterworks, which includes Stan Brakhage and Phil Solomon’s collaborative piece, Seasons. . ., Marilyn Brakhage, wife of the late filmmaker, was kind enough to answer Flicker Alley’s questions about the artist and his work as part of our Avant-garde Essay Series.

Flicker Alley: What was Stan’s typical work process? Did he have any creative rituals? Obstacles?

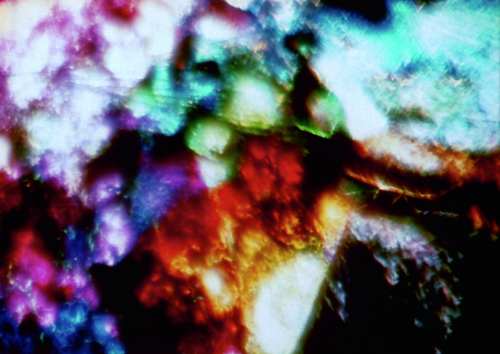

Marilyn Brakhage: There was always a lot of thought, a lifetime of study, of poetry, music, painting, film and vision, that you could say went into any and all of Stan’s work. But once he was working on a specific film, he would work in what he called “a trance state.” He would become deeply concentrated on what he was filming, painting, or editing, feeling his way through it, listening to “the Muse,” as he would characterize it; in other words, being deeply attuned and sensitive to the needs of the work itself, not imposing his will or any preconceived notions upon it, but letting it reveal itself. His task, then, was to “tell the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth,” and to “survive the process,” is what he would say.

Seasons… is included in our Masterworks of American Avant-garde Experimental Film 1920-1970 Blu-ray/DVD. How did the film come about in your memory?

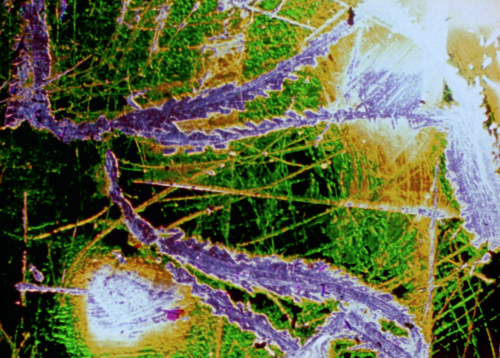

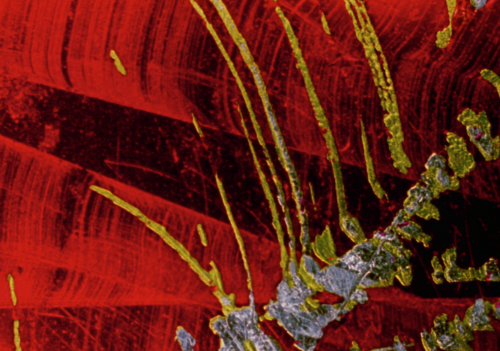

About eight years before Phil Solomon made Seasons. . . Stan and Phil collaborated on a film called Elementary Phrases. It was composed of hand-painted 16 mm film by Stan, arranged in patterns by him, step-printed, then, in a variety of ways, in close collaboration with Phil. The two of them then made a selection of these abstractions according, as Stan said, “to our shared sense of those which seemed to constitute ‘phrases’.” Stan then edited those into “something like ‘stanzas,’ five ‘lines’ apiece, each ‘line’ (or film strip) of which was separated equally in each stanza by black leader either 20 frames, 40 frames, or 60 frames — each stanza separated from every other by 60 frames of black.” Afterwards, they divided up the outtakes to be used by each as he wished. Stan then edited another little film a couple of years later, from these outtakes, which he called Concrescence. How the film Seasons. . . began I’m not exactly sure. Phil could tell you that. But it would seem that he had some ideas of his own that he wished to explore with the possibilities of variously optically printing and re-working Stan’s painting on film. For this, Stan provided him with some newly painted material, I believe, and Phil began working with it. There was a story that Phil casually mentioned at some point that he thought the film was needing a little more “summer.” Then a few days later, he found a small roll of painted film in his mailbox with the message: Summer, for Phil. However, all the optical re-working of Stan’s painting and all of the editing for Seasons. . . was done by Phil alone.

As you explained, Seasons... was a joint effort with Phil Solomon. How did Stan feel about creative collaboration in general?

When Stan first began to make films, at the age of 19, he worked with a group of friends, and continued to do so for several films (though after directing the first one, for subsequent works he did both the cinematography and editing on his own as well). He generally worked alone for most of his filmmaking life (though various other people appeared in his works, and showing the films and getting feedback from audiences was also crucial to him). He wasn’t opposed to collaboration, but there had to be a good reason for it. He worked collaboratively again on a series in the late ’80s, the Faust films, but even then, while there were actors and musicians and a painter involved, the filming and editing was all done by him. And in his few sound films, he most often edited film to a previously composed piece of music. Elementary Phrases was unique in his oeuvre, in that he worked so closely with another filmmaker, on the actual optical printing and selection of images. He did assist on several other short films afterwards, one with Mary Beth Reed and also contributing painting and assisting in the editing of a couple of films by Joel Haertling. But the work on Elementary Phrases stands out, to me, as an unusual coming together of two creative artists to create together a kind of visual conversation and composition on film. The solitary nature of Stan’s creative process would ordinarily have made this an unlikely eventuality.

What do you feel his attraction was to presenting his films, like Seasons…, as intentionally silent?

The reason that Stan made mostly silent films is that he was concerned with the deep exploration of all forms of vision, and of making what he called a “visual music.” Though his editing was often inspired by certain pieces of music, to then add actual music to the film would be like adding music to music. Any sound might tend to dominate over and influence how the images were seen, as his work did involve the intricate editing of multiple layers of micro visual rhythms. Several times, however, he did edit his film to music, but it was so precisely edited as to be a visual-aural conversation in which one would respond to the other on an equality of terms. He did not want to use music as ‘background’, nor for the images to be controlled by our experience of the sound.

Stan spent many years teaching at the University of Colorado. How do you think he viewed his role as an educator?

I think Stan enjoyed teaching (though he didn’t much enjoy the bureaucratic, administrative aspects of the university life). He also didn’t like the academicization of the arts, and viewed his role, I would think, as presenting artworks in combination and contexts that might awaken and inspire the sensibilities of his students. He challenged them, but he also listened to them and valued the give and take of aesthetic arguments and discussion. Discovering, studying, sharing and discussing art was his life — that is, when he wasn’t making art himself. And he was good at talking about it. So teaching was a natural extension of everything he cared about. When he wasn’t teaching at the university, he was often on the road lecturing and introducing his latest work.

In his later interviews, he seems critical of a new crop of professors who encourage students to make “easy movies” full of pop culture references and call them “profound art.” How do you think he would feel about the direction the experimental film scene has taken today?

I rather think he would lament the loss of celluloid film in an increasingly digitalized world, as the visual experience of the rhythms and colors and textures of film are completely different, and an understanding of that difference is being lost. Beyond that, as there is such a variety of work being done, I’m sure that he would be able to find young filmmakers whose work he cared about. If it was truly personal and made with all honesty out of a deep inner need, he would recognize that and honor it. But if it seemed like superficial trickery — then obviously, not so much!

Even when recognized as groundbreaking and innovative, many avant-garde films have trouble finding commercial success, leaving many gifted artists to struggle financially. What was Stan’s attitude toward this tension between art and commerce?

The artist, in Stan’s view, would have to follow the demands of the art, with no commercial view in mind, in the making of the work. However, he thought artists ought to be paid, certainly. If the museums want to show the work, then they should pay for it. If people want to see the work, they should pay for it. Because, after all, artists need to eat, and live, like anyone else.

How do you think Stan’s work has influenced mainstream cinema today?

I think Stan and a few other avant-garde filmmakers were very influential in the evolving styles of camera work and editing that are now commonplace in commercial movies. But I don’t actually, myself, think that the influence on mainstream cinema is what is most interesting about these avant-garde films. Even after many decades, they remain powerful, crucial, visionary experiences that open new worlds of vision for anyone who cares to truly see them. They have their own life. I am reminded of how Stan quoted Ezra Pound, in reference to his series of films called the Songs: Go little naked and impudent songs / Go with an impertinent frolic! / Say that you do no work / and that you will live forever.