by Charles Epting, author of University Park, Los Angeles (Brief History)

My name is Charles Epting. I’m 21 years old, and I almost exclusively watch silent films.

That is a fact that is often met with incredulity by my peers. Most people think I’m joking when I tell them about my love for the silent era. Others assume I must watch silent movies in the same ironic spirit that compels hipsters to listen to vinyl and wear bow ties. More often that I’d like to admit, people figure that I must only be referring to The Artist.

But the truth is, silent movies have become such a part of my life I don’t even look at them as silent anymore—to me, they’re just “movies.” I’m more comfortable flipping through an vintage issue of Photoplay than I am a modern issue of People. Figures such as Fairbanks and Gish are still larger-than-life to me, despite the fact that we weren’t even alive at the same time.

This essay is simply a chance for me to put my thoughts down on paper about what it’s like to be a millennial who is fully invested in the silent era. With any luck, it might inspire others my age to take the same journey I did into the earliest days of Hollywood.

❃ ❃ ❃

I don’t remember the first time I saw a silent film. Throughout my childhood my dad would explain to me the brilliance of Charlie Chaplin, but the only movie of his I recall seeing at a young age was The Kid. Don’t get me wrong, I loved it, but it didn’t spark any desire to seek out more silent films. I simply looked at it as a classic, in the same category as Casablanca and King Kong, and that was that.

As I got older I had a passing familiarity with names like Harold Lloyd (he was the guy hanging from a clock) and Buster Keaton (he was the guy who never smiled). It all comes back to the Mark Twain quote that a classic is “a book which people praise and don’t read.” I looked at films the same way. If everyone thought that Buster Keaton movies were brilliant then there must be some truth behind it—I just never cared to search for that truth.

As cliche as it sounds, my first true forays into the world of silent films were a result of an obsession with the 1920s inspired by—you guessed it—reading The Great Gatsby. I still remember going to my university library as a freshman one evening to check out two films: Keaton’s The General, and Chaplin’s The Gold Rush. The next day I went back for Lloyd’s Safety Last. I had heard they were the holy trinity of the silent era—so their most popular movies would be as good a starting point as any.

It may sound crazy, but I was instantly hooked. It would be a while before I picked up on the nuances inherent to the genre—I’m still learning how to watch silent films—but my initial impression of all three actors was sheer brilliance. From Lloyd’s timing to Chaplin’s elegance to Keaton’s physicality, I had never seen anything quite like those films. And to this day, I can’t watch The Gold Rush’s “dinner roll” scene without tears of laughter streaming down my face.

❃ ❃ ❃

My roommate freshman year was notorious for the parties he threw in our apartment. Late one night, in the middle of one such soiree, he came into our bedroom to find me glued to my computer watching Safety Last.

“How can you watch anything with the amount of noise we’re making out there?”

An unforeseen benefit of silent films—and a critical one as a college student, where peace and quiet can be a luxury.

❃ ❃ ❃

From those first three films, it didn’t take long before I became more adventuresome. I quickly delved into Keaton and Lloyd’s catalogues, where I discovered the two silent films that remain favorites of mine to this day—The Navigator and Girl Shy. The horror fan was excited to watch such masterpieces as Nosferatu and The Cabinet of Dr Caligari. I was constantly challenging myself to discover new actors, new directors, new genres.

I was also surprised to learn that I had been surrounded by silent movies my entire life without even realizing it. Every day on my way to class I walked past a statue of Douglas Fairbanks, who founded by university’s cinema school. I had never so much as glanced at it before—now I can’t walk near the Thief of Bagdad himself without stopping in admiration. Next I found out that one of my favorite bands—The Smashing Pumpkins—had released an album entitled Gish after a silent film actress. I quickly watched Way Down East and Orphans of the Storm.

❃ ❃ ❃

One day I arrived at my classroom so early that the prior class—an ethnographic studies course—was still in session. I sat down in the back row and caught the end of a lecture about how racially insensitive D.W. Griffith’s Broken Blossoms is. After the class was dismissed, I found myself alone in the room with the professor, who was gathering her belongings.

“Don’t you think it’s a bit unfair to Mr. Griffith’s legacy to impose 21st century morality on a film nearly a century old? Besides, while the depiction of Asian culture in undoubtedly stereotypical, I think it’s important to note that of all the film’s characters, Richard Barthelmess’s [Cheng Huan, a Chinese man] is portrayed in the most positive light.”

I still don’t know where that rant came from, but the professor was speechless—not at the point that I had made, but at the fact that I had seen Broken Blossoms multiple times. It was at that time that I realized how much silent films meant to me.

❃ ❃ ❃

In today’s world of constant social media and invasive technology, of incessant bombardment by advertisements, of smart phones and tablets, there is something immensely refreshing—for me at least—in the subtlety of silent movies. In the absence of dialogue, it becomes key to study facial expressions, lighting, setting—things that might otherwise be lost on a moviegoer.

My generation is impatient. We’re a generation of instant gratification, and the pacing of silent movies is in direct contrast to what we’re used to. I suppose that’s why old movies in general have a reputation for being “boring,” which is something I’ve never understood. We’re a generation of viral YouTube videos and binge-watching Netflix, so the concept of sitting through a three-hour silent epic like Birth of a Nation is preposterous to anyone my age.

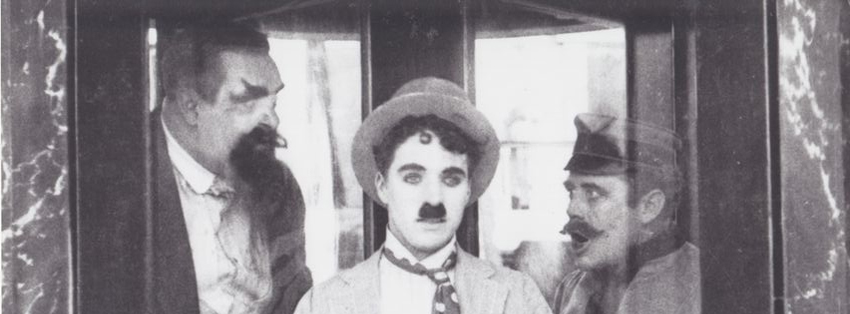

We’ve become so conditioned to expect to be “wowed” at the movies—I refer to it as the James Cameron Syndrome. And that’s not to say that silents can’t take your breath away (see the Babylonian scenes in Intolerance or the bridge collapse in The General). But these are exceptions, not the norm. Instead, silent movies were largely driven by actors and directors with no CGI to hide behind, nothing flashy to superficially impress audiences. Charlie Chaplin could make an audience laugh and make an audience cry with nothing more than his face and a silly outfit.

I’m not going to lie and say all silent films are brilliant. Like any other period of filmmaking, there’s silent movies that are genius and silent movies that are hard to sit through. I was so excited the first time I watched Olive Thomas’s The Flapper—after all, what could be more indicative of the Roaring Twenties than a movie named after the era’s most famous trope? But despite the mystique surrounding the film (Olive would be dead 4 months after its release), it’s simply not a very good movie.

But for the most part, even the worst silent films have something redeeming. A glimpse into 1920s life, an early appearance by a famous actor or actress, an unprecedented technological breakthrough—I have yet to see a silent movie that didn’t have something appealing in it. It’s for this reason that I’m constantly tracking down new movies to watch. Next up for me is Wild and Woolly, an early Fairbanks western.

❃ ❃ ❃

There’s an honesty in silent films that I have yet to find in any other era. Maybe it’s because Hollywood was still so young. It might just be my habit of overly-romanticizing the past, but I feel like the fledgling film industry had an excitement, and earnestness, that would never again be matched. There’s such a contrast to the jaded cynicism we see in Hollywood today. I have nothing to back up this claim, but it’s a feeling I’ve had ever since I first saw Harold Lloyd hanging from the clock face in 1923.

I realize that silent films aren’t for everybody. I’m used to the disbelief when when a Gen Y’er cites Bessie Love and Bebe Daniels amongst his favorite actresses. But for me, it seems like the most natural thing in the world. Silent films aren’t dinosaurs of the film world, extinct because they’re too primitive and stupid. Instead, they’re vibrant glimpses into the newborn world of Hollywood, fleeting sights into a bygone world before dialogue.

❃ ❃ ❃

Not too long ago I was sitting on the couch with my 9 year old cousin when The Dark Knight came on TV.

“Do you like this movie?” he asked me, with full confidence I would say yes.

“To be honest, I’ve never seen it before.”

“Well what kind of movies do you like then?”

Unsure of how to explain the silent era to an adolescent, I simply responded, “I like to watch really old movies.”

“Oh, you mean like Titanic.”

All I could do was smile.

Charles Epting is a recent graduate of the University of Southern California, and is planning on pursuing a doctoral degree in history. In addition to being an avid silent film fan, he is the author of four books on Southern California history and is currently working on a biography of a silent film star. His book University Park, Los Angeles (Brief History) includes an extensive chapter on the early days of film at USC and is available to order on Amazon.