The National Board of Review’s Committee on Exceptional Motion Pictures reviewed three experimental films by Maya Deren for their March 1946 issue of New Movies magazine, including Meshes of the Afternoon, part of Masterworks of American Avant-garde Experimental Film 1920-1970. While it seemed as if the experimental film movement had died with the Great Depression, the reviewer declares that “This somewhat condescending epitaph on the experimental film is now disavowed, if not cancelled, by a new and emphatic voice,” Maya Deren.

“She states emphatically, what every film-lover knows, that movies must be visual from the first conception, not translations of verbal images into visual— that themes must be given form by a use of the total resources of the medium, still largely unexplored. And that films can be poetic, lyrical, as well as dramatic and instructive. Provocatively she denounces us all for our passive acceptance of the commercial film set-up as the only possible one, and sounds the clarion for the film which celebrates experience on a level with the older arts.

All this, familiar as it is to film students, has stirred up a minor maelstrom of controversy, Miss Deren its serene storm center. But she is not interested in shocking the bourgeois, as many of her predecessors have been. She is in earnest—the films and her voluminous writing about them prove that. And both she and the films have much of interest to offer.”

Read the full text below.

Full Text:

THREE EXPERIMENTAL FILMS

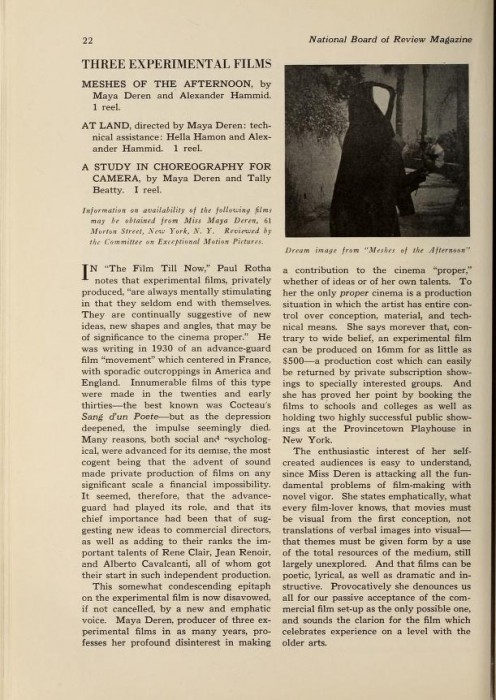

MESHES OF THE AFTERNOON, by Maya Deren and Alexander Hammid. 1 reel.

AT LAND, directed by Maya Deren: technical assistance: Hella Hamon and Alexander Hammid. 1 reel.

A STUDY IN CHOREOGRAPHY FOR CAMERA, by Maya Deren and Tally Beatty. 1 reel.Information on availability of the following films may be obtained from Miss Maya Deren, 61 Morton Street, Neio York, N. Y. Reviewed by the Committee on Exceptional Motion Pictures.

In “The Film Till Now,” Paul Rotha notes that experimental films, privately produced, “are always mentally stimulating in that they seldom end with themselves. They are continually suggestive of new ideas, new shapes and angles, that may be of significance to the cinema proper.” He was writing in 1930 of an advance-guard film “movement” which centered in France, with sporadic outcroppings in America and England.

Innumerable films of this type were made in the twenties and early thirties—the best known was Cocteau’s Sang d’un Poete —but as the depression deepened, the impulse seemingly died. Many reasons, both social and psychological, were advanced for its demise, the most cogent being that the advent of sound made private production of films on any significant scale a financial impossibility. It seemed, therefore, that the advance-guard had played its role, and that its chief importance had been that of suggesting new ideas to commercial directors, as well as adding to their ranks the important talents of Rene Clair, Jean Renoir, and Alberto Cavalcanti, all of whom got their start in such independent production.

This somewhat condescending epitaph on the experimental film is now disavowed, if not cancelled, by a new and emphatic voice. Maya Deren, producer of three experimental films in as many years, professes her profound disinterest in making a contribution to the cinema “proper,” whether of ideas or of her own talents. To her the only proper cinema is a production situation in which the artist has entire control over conception, material, and technical means. She says moreover that, contrary to wide belief, an experimental film can be produced on 16mm for as little as $500—a production cost which can easily be returned by private subscription showings to specially interested groups. And she has proved her point by booking the films to schools and colleges as well as holding two highly successful public showings at the Provincetown Playhouse in New York.

The enthusiastic interest of her self-created audiences is easy to understand, since Miss Deren is attacking all the fundamental problems of film-making with novel vigor. She states emphatically, what every film-lover knows, that movies must be visual from the first conception, not translations of verbal images into visual— that themes must be given form by a use of the total resources of the medium, still largely unexplored. And that films can be poetic, lyrical, as well as dramatic and instructive. Provocatively she denounces us all for our passive acceptance of the commercial film set-up as the only possible one, and sounds the clarion for the film which celebrates experience on a level with the older arts.

All this, familiar as it is to film students, has stirred up a minor maelstrom of controversy, Miss Deren its serene storm center. But she is not interested in shocking the bourgeois, as many of her predecessors have been. She is in earnest—the films and her voluminous writing about them prove that. And both she and the films have much of interest to offer. For one thing, the three films are technically superior to their fore-runners. Makers of experimental pictures have not infrequently been innocent of technical experience, their films murk-photographed, jerkily edited, the lighting and action oddly assorted from scene to scene. This uncertain technique produced a kind of unconscious surrealism, but it left the intended effect somewhat at sea. But Miss Deren has had the advice and assistance of her husband, who as Alexander Hack-enschmied directed or photographed such admired documentaries as Crisis, Forgotten Village, and Valley of the Tennessee, with the result that her films have a technical facility that is almost elegance. The numerous photographic and editing devices— conspicuously skillful is the use of stop-motion photography — are designed to build a new reality out of the separate elements of phenomena, and they accomplish their imagined universe with style and grace. As examples of technique, all three films merit the attention of new students of movie aesthetics. They could, in fact, be conveniently used in appreciation courses as compendia of the resources of the medium.

“Because they exemplify so many devices, it may be said of them that they escape eclecticism by a hair’s breadth. Their content is indeed eclectric, a reprise of thematic material made familiar by many advance-guard films of the past. Meshes of the Afternoon begins with a girl returning to her home and falling asleep in her chair. Her subsequent dream re-works the events of the afternoon into an experience expressive of her unconscious impulses. At Land apparently occurs altogether on the subliminal level, and is described as “a film in the nature of an inverted Odyssey, where the universe assumes the initiative of movement and confronts the individual with a continuous fluidity toward which, as a constant identity, he seeks to relate himself.” The Study in Choreography, while not exactly subjective, also strives to detach the spectator from his material moorings: “together the dancer and space perform a dance which cannot exist but on film.” The fact that all three films contain so many echoes of past experiments is not unexpected. The urge to explore the resources of film has most frequently accompanied a fixed interest in states of mind, in imagination and sentiment for their own sake rather than as spur to action. The danger that lies in wait for the experimental film-maker with this approach is the danger of abstraction and of obviousness. Individuals tend to become archetypes, emotions are rendered upper-case, photographic devices are used so continuously as to become ostentatious, and it is a very self-conscious Unconscious that is revealed to us. It is an odd fact that the best and most poetically subjective films have come not from the experimentalist but from the commercial and propaganda fields. In the work of von Stroheim and Pabst, of Griffith and Dovzhenko and Basil Wright, objects have a life of their own and the universe is seen in constantly shifting guise, but this is a matter of accurate observation and subtlety in cutting and camera position, rather than of arcane trickeries. But it is no discredit to Miss Deren’s films that they challenge comparison with the masters, and insist on doing so in their own way. On the contrary. As Rotha said so many years ago, they jerk us alert, make us reexamine our convictions to find if we are truly so convinced as we thought, and force us to think through all over again the right function of this extraordinary instrument that we have in the film. For new converts to the medium they should be especially stimulating, and it is comforting and rather startling to discover that their maker is determined that they shall find that audience. – R.G.

Source: New Movies, National Board of Review Magazine, March 1946

Maya Deren’s Meshes of the Afternoon is one of 37 films in Masterworks of American Avant-garde Experimental Film 1920-1970, now available on Blu-ray/DVD.