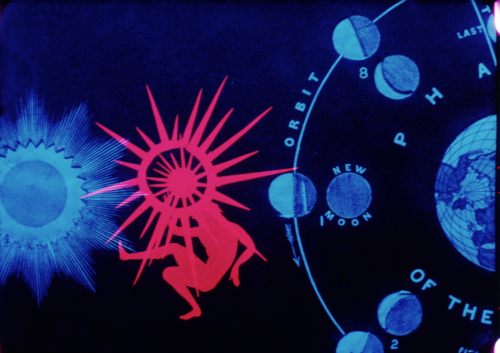

Experimental filmmaker and artist Lawrence Jordan is known as a maverick spirit in the avant-garde world. A key figure in San Francisco’s avant-garde art scene in the 1950s-60s, Jordan also played a pivotal role in the expansion of the Film Department at the San Francisco Art Institute, where he taught for over 30 years. Our Lady of the Sphere (1969), his magical collage animation produced from line engravings and cutouts, is featured on Masterworks of American Avant-garde Experimental Film 1920-1970, as is Thimble Theater, one of the several Joseph Cornell films completed by Jordan.

In the Flicker Alley exclusive interview below, Mr. Jordan discusses the dream-like magic of his films, his friendship and working relationship with filmmaker Joseph Cornell, and the evolution of the San Francisco avant-garde art scene.

FLICKER ALLEY: You’re known for your animated collage films, like Our Lady of the Sphere. What drew you to this technique? What about it allows you to best express your “underground” or unconscious?

LAWRENCE JORDAN: I don’t like drawn animation very much, but there is a tension between the stiffness of a cutout and the motion. Also, I like the fact that I can use a lot of things that should not move and make them move. It forms a magic that I’m rather addicted to.

In your animation, you seem to cull a lot of your material from the realm of fairy tales and European baroque paintings. Is taking from fairy tales part of that “magic”?

Well, it’s one small part. I draw inspiration from just about everything I’ve contacted or read, from physics to fairy tales. I would say that most of the materials is illustration from the 19th century, not because I’m particularly nostalgic, but because the engravings photograph so well. There’s no halftone, so there’s more snap.

More recently, I was able to use colored photography out of magazines, which I never had been able to use before, and found that I could do things with that as well.

Was this new development thanks to a change in technology?

Yes, in a way, because Eastman has produced very excellent color negative in 16mm, but that’s been around for a long time. So no, technology is not the reason. It’s me. It’s me, seeing differently.

Your work is heavy with symbols and archetypes. Are there symbols that stand out to you in particular? Or that you find yourself coming back to over and over again?

There are, but I only know them when I see them. They’re not really describable. They come out being somewhat universal, rather than personal, and that’s worked better for me. For example, using a lot of round objects. That’s just a universal symbol; it’s not a personal symbol. What I tend to be attracted to are things that have wide significance somehow. Sometimes it’s animals; sometimes it’s microscopes. Who knows?

“Dream-like” is a common descriptor of your films. Do you ever work directly from your own dreams?

These films are not like my dreams. It’s a waking animation. Doing animation is like seeing in slow motion. There’s a kind of meditative joy in being able to craft the motion bit by bit.

In Our Lady of the Sphere, collage is not only a visual experience; it’s audio, as well. How do you work with sound in your films? And what is the relationship to the imagery?

[Our Lady of the Sphere is] still one of the tightest marriages between the sound and picture that I’ve been able to effect. I got into an area of shooting a lot of footage, then looking at it and cataloging it on paper, and then constructing the film on paper down to the frame. And also applying sound to the construction on paper. Then cutting it and recording it the way that I had made the architectural diagram of the film. And somehow, it worked.

I haven’t ever worked in that same way again. I don’t like to work the same way over and over again. Each time the process is different or else it’s no fun. Sometimes it comes out better than other times.

After corresponding for a few years, Joseph Cornell invited you to be his assistant. What was it like living with the filmmaker? How do you feel that experience influenced your work?

Very early on, when I was young, I was aware that I thought Cornell’s work was the best art I’d ever seen. I’m also attracted to the surrealist, but not the part of surrealism that tries to get under the skin and wake up the viewer with uncomfortable imagery. The part that I’m attracted to is the timelessness that Cornell exemplified.

I met him in about 1955 in New York and then went back to California and corresponded for 10 years. We did some collaboration through the mail – photography, and he would send me a film now and then to look at that he made with Rudy Burckhardt. Then in 1965, I went back to New York [to assist Cornell].

I edited a film that Burckhardt had shot that we called A Fable for Fountains (or Legend for Fountains). We were very much into film at the time I helped him. We were also doing boxes, and he was doing collage as well.

[Cornell] told me he had stopped making films because he didn’t know what to do with them. He gave some to Anthology Film Archives, and he gave me a shoebox full of small reels of 16mm film which I took back to California. When I started going through it, I found 3 reels that were edited. Those are the three that I call “3 by Cornell.” I worked on those, re-sliced everything, got them so they would run through a printer and tidied everything up.

Later, I found 3 more reels, and Thimble Theater was among those. There was a little tiny note about sound possibility. so I put that together.

The experience of working with Cornell was very strange because I would be down in the workroom editing, and he would come down and look at a sequence and say, “Well, I don’t agree with what you’ve done there,” say nothing more, and go away.

So I’d say, “Okay,” and take that apart. Then say, “Now what would be more like a Cornell film?” and take things apart and rework it.

He’d come down and say, “Well, I think we can work with that.”

The way his films are edited, they don’t make snappy sequences. It’s just an image and that leads to another image and somehow that adds up. It’s really not easy to explain what the construction of a Cornell film is, but it proceeds in some kind of imaginary world that is more or less “timeless” – He used that word multiple times. He was always trying for work that was timeless. It was a matter of keeping the images afloat and never making them hard-driving, like in most films. And then he’d be satisfied.

In order to edit his films, it sounds like you really had to know Joseph Cornell well to be able to anticipate what he would want.

That’s right! You had to pick up the “unspoken radiation.”

We spoke with Shirley Clarke’s daughter about the New York avant-garde film scene of the 1960s and of Jonas Mekas’ filmmakers collective. She describes the culture as a wild, but small, tight-knit, supportive community of artists. How would you compare the San Francisco art scene of the same era?

In the early days, in the ‘50s, when I came to San Francisco, the art community was fairly small and you tended to know everybody. You tended to know who was doing what, when and when there was going to be a show. An awful lot of the community would turn out when we’d have a show.

Then in the late ‘50s, it got very intense. It was indescribably intense.

Competitive?

No, not competitive at all. The exact opposite. Everybody was supportive of everybody else. Everybody was interested in what poem Philip Lamantia or what painting Nemi Frost had just finished. When there was a show in my garage a lot of people would come. No, it was alive. It was just totally alive.

And then going into the ’60s, it got all fractured by the hippie thing, but it kept going.

By the 1970s, things were getting institutionalized, in the schools, in the museums. The fervor was cooling down quite a bit. But I should add that people left San Francisco, North Beach particularly, and went to Oakland, went to Stinson Beach, went to Venus, went to San Rafael – and the people that survived became very good artists working alone then.

Tourists moved into North Beach and the “scene” was gone. People went on back to New York and Los Angeles where they had come from.

What led up to your founding the Film Department of the San Francisco Art Institute in 1969? What need did you feel was not being fulfilled on campuses? What did you feel was your responsibility toward your students?

I didn’t found [the department] from the beginning. Robert Nelson was there before I was, but he left very soon after I started teaching there. I was the one who expanded it from one classroom and one projector into a film department. I was the architect of what the film department became. You could hardly call it a department when I went in, but then we had the best filmmakers in the country – many of them, not all of them of course – teaching there, and that lasted about 12 years.

My vision before I was teaching there – I renovated and set up a 16mm theater in San Francisco because there just wasn’t anyplace to show our films. That was the same vision I had when I started teaching: to make a place where filmmakers could find equipment and start making films, with some instruction on how to do it.

You taught at the school for over 30 years. What changes have you seen take place? What is your relationship with past students?

Some of the students in the ‘70s were incredibly good. Beth ran her own Buddhist film company in Holland and Ashley James started his own film company called Searchlight Films in Berkeley and was also the manager of a television station. John Davis is my collaborator and also writes music for my films and is the projectionist at the MoMA. These are all ex-students who are now teaching me the digital world. So it’s come back. Those early students are still very active and we’re still in touch.

Is digital something you see yourself pursuing?

Well, I will never photograph digitally, but we make all the soundtracks digitally now, so my films at present are hybrid. I went in the day before yesterday and we digitized my latest film. We’re going to construct sound digitally in a sound studio in a couple weeks and get them put together.

The picture is on film still, but the sound is pretty much these days digital. Both Ashley James and John Davis are just total experts in the digital world.

Finally, what attracted you to the world of filmmaking in the first place? Who are some of your heroes?

Max Ernst, Luis Buñuel, Jean Cocteau. Those are the main ones.

Lawrence Jordan is an avant-garde filmmaker most widely-known for his animation collage films. In addition to making over 50 experimental films, Jordan has completed several unfinished works by filmmaker Joseph Cornell. More information about Jordan’s celebrated career can be found at http://lawrencecjordan.com/.

Our Lady of the Sphere and Thimble Theater can be found on Masterworks of American Avant-garde Experimental Film 1920-1970 ,now on Blu-ray/DVD.

For more exclusive interviews like this one, plus film preservation news and special discounts, sign up for the Flicker Alley Newsletter.