Daughter of acclaimed independent filmmaker Shirley Clarke, Wendy Clarke grew up immersed in the avant-garde art film culture of New York in the 1960s. Her wedding is the focus of the “Wendy’s Wedding” vignette in Jonas Mekas’ Walden: Diaries, Notes and Sketches (1969) and is included in the Masterworks of American Avant-garde Experimental Film 1920-1970 Blu-ray/DVD collection. Unlike a traditional wedding scene, Mekas presents a wedding reception that is fast, frenetic, and uncontrolled; a rapid-fire barrage of sound and images. Ms. Clarke was kind enough to sit down with Flicker Alley to share her memories of the experimental filmmakers of 80 Wooster Street, the role gender played in the her own career and that of her mother’s, and the transition from film to video and beyond.

FLICKER ALLEY: Walden is considered to be an accurate portrayal of that time and those artists. What was it like growing up in that environment, surrounded by the great filmmakers of New York’s avant-garde/experimental film scene?

WENDY CLARKE: I’m so glad that I was alive during that time and that my mother was my mother. It was an incredible gift that I got to meet these people. Everyone was very generous with each other. My mother would host dinner parties all the time, and they would show their films to each other. I was just a child and would sit on the couch and watch.

My memory of it is that it was pretty wild and crazy and interesting and intense. I saw Maya Deren put a curse on Stan VanDerBeek. All the people were such unique characters. Very individual and poor for the most part. They were all interesting looking and had interesting accents and were extremely eccentric – and that was a good thing.

I remember going to Berlin in the ‘60s. They were invited to Germany and I tagged along with my mother [filmmaker Shirley Clarke], Stan VanDerBeek, Bruce Connor, Stan Brakhage, and a few others. I had the best time with Bruce Connor; we became really good friends in Berlin.

I remember Stan Brakhage taking his camera and going to these places where there are no lights, like a club or street, and saying, “This is what it was like.” The film must have come out almost black! I remember sort of laughing at that and thinking it’s absurd and so dramatic, but it’s artistic.

I do remember seeing Jonas Mekas around with a camera, but he was very good at being non-obtrusive. He was definitely the driving force of that movement in his quiet.

How does your own memory of your wedding compare to how it was portrayed in Walden? The film seems to attack your emotions and play with the passage of time. Do you think there’s an emotional truth to the way its represented?

It’s very similar to what I remember: Crazy-making.

I do think that the way that my wedding was portrayed was pretty accurate in an artistic way, not in a documentary way. Because it’s a journal, so it’s [director Jonas Mekas’] experience of that time.

Jonas was very quiet so you didn’t know he was there a lot. He was the perfect person to do this because he never took over and his presence was always somewhat removed. Very nice, but not active, not in front of your face.

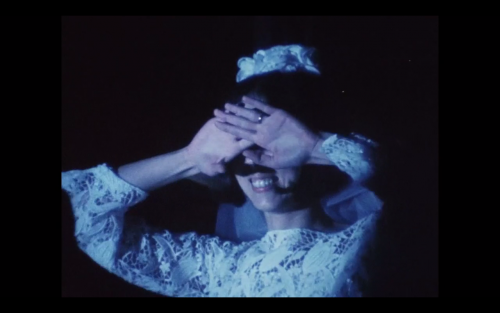

The wedding “of the time.” My mother [filmmaker Shirley Clarke] sort of did it all. It was her doing, I have to say. The strobe light and all the bands. My grandmother have to leave and a couple friends couldn’t take the strobe light.

[Avant-garde filmmaker] Barbara Rubin did all the decorations. I just remember thinking that it looked like whorehouse in heaven. It was blue and pink tulle. There were all these streamers – it was just billowing tulle. A big Jewish deli on the Lower East Side catered it, and my husband of then was a bartender, so he got black champagne for cost.

It seemed chaotic.

It was pretty chaotic from the strobe light.

Archie Shepp, the jazz musician played, and Adolfas Mekas’ wife sang. I don’t know where that music [in the scene from Walden] came from.

It may have just been that it was bad sound. There were tons of people there. Good friends of my father and future step-mother gave me an ancient Jewish menorah – and somebody stole it. It was pretty cuckoo. I don’t know if people came off the street. I saw tons of people I knew, but I’m sure there were tons of people there that I didn’t know.

Your wedding took place at 80 Wooster St. [DEFINE IT] Was that kind of chaos par for the course there?

[The artists’ collective] had just gotten 80 Wooster St. They hadn’t moved in their stuff yet. We sort of christened it with the wedding. I’m sure that we got to do it because they hadn’t moved in yet, so we had this huge empty space.

Jonas’ places kept moving around the downtown area. I remember going to, if not all of them, most of them. It just evolved into Anthology [Film Archives].

The first time I ever met Babara Rubin [was at a previous incarnation of 80 Wooster St.] I remember walking upstairs and there was this little loft and Flaming Creatures was being shown and Barbara Reuben was sitting on a stool at an editing area rewinding film, and she was topless.

Walden is a diary. At that point in time, Jonas Mekas felt the best way to express his own diary was through 16mm film. You and your mother, Shirley Clarke, worked a lot in video. How do you feel about the changing formats and how they relate to expressing one’s emotions or relaying personal events?

It’s so interesting because I experienced all of those changes [in format]. My own creativity didn’t work that well with film, whereas video was really ideal for me because of the immediacy of video, being able to see yourself as other people see you in that moment, being able to have the medium really affect you in both a very emotional and kinetic way. In every kind of way.

For me, film was more removed. I had worked on some films of my mother’s in the editing room, I also worked for a while for [Albert and David] Maysles in their editing room and on Woodstock in the editing room. I hated it. It was just as bad as being a secretary. It was horrible and tedious and just not fun.

With film, it takes lots of other people. It costs a lot of money. Video has an immediacy, and you can do it yourself. It was a wonderful time to experiment. It’s still like that; video is more of a medium of the people. Though I haven’t been actively working in video since I moved here to New Mexico. I felt that for me, I was active at the best time for experimenting with video. It was really before things were working well with it, so you could use your imagination and try things that nobody had ever tried. There was something about that that I found very enticing. I really enjoyed it, and then I reached a place where I didn’t want to play with it anymore.

It was annoying to have the format keep changing. It still is. Right now I’m trying to get the Love Tapes to be digitized and it’s every format. I also have a video diary that I kept religiously for 10 years. Hundreds of tapes of me talking to myself. And they’re probably dust. I thought that one day I’d like to work with them, but I don’t know if there’s anything left.

Your mother Shirley Clarke was a very influential female avant-garde and documentary filmmaker. How do you feel that gender politics has influenced her career and your own?

I think gender did influence her career, more so in hers than in mine. I think there were a number of reasons why she didn’t make more films. It wasn’t just that she was a woman, but that was a big reason. At the time, there weren’t other women film directors. I’m not sure what the numbers are now, but I’m sure it’s not 50/50.

I never found my mother to think that she couldn’t do something because she was a woman. I never saw that enter her being. I think for people who are committed and driven and passionate about something, it’s not a matter if you’re a man or a woman. It didn’t seem to stop her creativity, certainly, but I think it did think it stopped her from being successful.

It was very horrible for her when she went to California. There was she in Hollywood. I don’t think it ever would have really worked, because from what I understand about how Hollywood films were made, as a director, you lose a lot of power. I remember what Jim McBride had to go through to make films. They wanted him to change the ending, etc. It was horrible for someone who thinks of the piece you’re making as a creative work of art.

I just remember the struggle that my mother had. She had so many scripts that she tried to get people to do. She wrote a script with Shelley Winters, and they couldn’t get it produced. She wasn’t “regular;” she wasn’t commercial. I remember her dealings with Roger Corman, who made all those “not that good” films. She really tried to make a film with him, and it didn’t work out. I’m sure that a piece of that was that she was a woman.

She was a huge fighter for women. It’s still something that hasn’t worked itself out in our culture. It continues.

I have not found it to be an issue in my own life. I think part of that was because of my mother and father instilling in me that it was fabulous that I was a girl. It was the best of anything. In that way, I lucked out. I didn’t see either one of my parents think that women were of the lesser creatures on the planet. I’m sure that was a foundation for good confidence.

In addition to making films, Jonas Mekas and the avant-garde community at large has focused on film curation. What do you feel drives this connection between experimental film and curation?

Avant-garde or experimental film was always looked upon as art. That’s why you have curators and museums. The curators were critically important in determining whose work was seen. Because we didn’t have YouTube. My memory is that there were very tiny audiences for all of this stuff. Which was not fun, but it was always considered art. The people who got into video later came from other art backgrounds, from dancers, painters, theater people. It was definitely in galleries, and art galleries were all curated.

The curators were “all powerful.” Barbara London and John Upton – If they didn’t like your work, you didn’t get shown in the MoMA, the Whitney.

There was also less commercial possibility then than there is now, from what I see of people who have these YouTube followers. I’m not sure how many people make money from it, but they certainly get a very wide audience

Way fewer artists were doing this then. Because now anybody does it, in a way. It was a very tiny circle in New York. My mother threw really great New Year’s Eve parties, and they all came to it. You knew everyone. There weren’t hundreds then, and now there are millions.

Independent video artist Wendy Clarke’s work has been exhibited internationally on television and in museums, galleries and public places. She conceptualized and produced “Love Tapes,” an interactive video series which documents individuals’ personal definitions of love. The critically-acclaimed project now consists of over 800 short videotapes accumulated over 30 years. “Love Tapes” and several other projects can be accessed at UCLA’s Wendy Clarke Collection of Video Art. Ms. Clarke currently resides in New Mexico where she is exploring textiles and fiber artwork.

“Wendy’s Wedding” from Walden: Diaries, Notes and Sketches can be seen in the Masterworks of American Avant-garde Experimental Film 1920-1970 Blu-ray/DVD collection. Now available for Pre-Order.