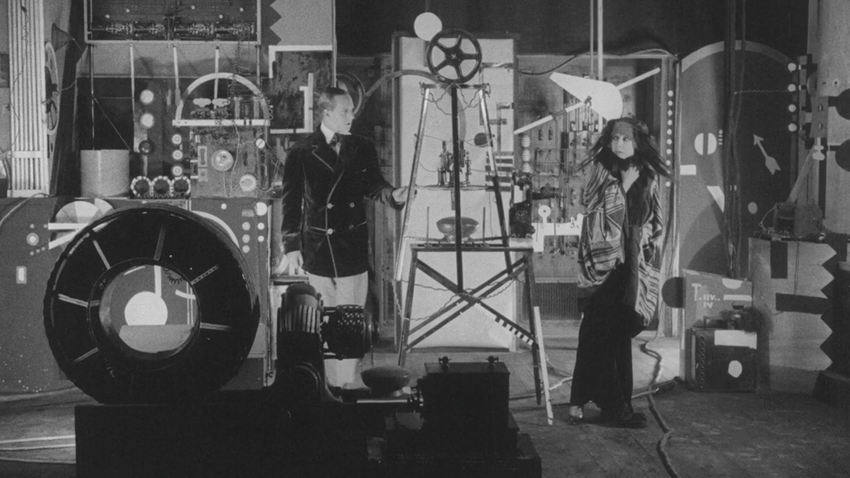

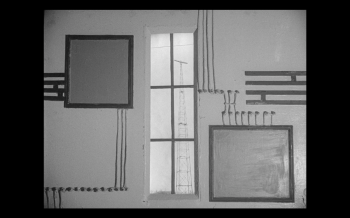

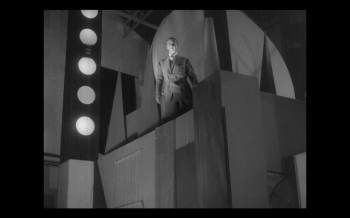

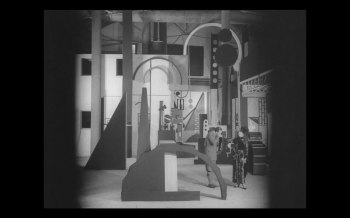

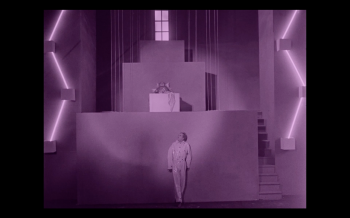

French filmmaker Marcel L’Herbier’s groundbreaking contributions to cinema helped to define the country’s “first” avant-garde or “Impressionist” movement, which began to take shape in 1917. While his futuristic fairy tale L’Inhumaine (1924) is lauded as an Impressionist masterpiece, in a way the film’s production also laid the groundwork for the end of the very Impressionist movement it represents. For L’Inhumaine‘s production, L’Herbier recruited a team of artists from all mediums to represent the cutting-edge trends in every artistic domain. One of these artists was painter Fernand Léger. Léger contributed to L’Inhumaine‘s the set design and conceived and animated the opening credits. Léger’s participation in L’Inhumaine, which forced him to adapt forms, colors, and sizes to the eye of the camera, sharpened his thinking about cinema, which had captivated him for a long time. This led in 1924 to the shooting of his famous Ballet Mechanique, an experimental short film co-authored with Dudley Murphy. In his essay, “French Avant-garde Film in the Twenties: from ‘Specificity’ to Surrealism’,” Ian Christie describes the pivotal role Ballet Mechanique played in marking “the (delayed) encounter between modernism and the cinema.”

Léger gained direct experience of the avant-garde cinema when he was invited by L’Herbier to design the laboratory sets for L’Inhumaine, a futuristic melodrama which also involved architectural designs by Robert Mallet-Stevens. Léger designed the laboratory and a poster in his ‘machine’ style; and later Ballet Mechanique was shown with L’Inhumaine in New York. Ballet Mechanique, however, made in collaboration with the cameraman Dudley Murphy, marked the decisive instance of modernism in the cinema. In the first place, it abandoned narrative and analogical structure in favor of analytic form: the episodes and their juxtaposition were determined by the kinds of filmic material involved. Secondly, the film took as its problematic the cinema as a means of reproduction and representation, thus re-inscribing the terms of its own production. Within this overall modernist shift, Ballet Mechanique also managed to re-locate the central themes of the Impressionist avant-garde and develop them coherently. Thus Léger’s close-ups of domestic items demonstrate the effect of photogenie with familiar objects, while the use of prisms, mirrors and other optical transformations provides an inventory of modes and abstraction within the filmic image – but one belonging to the twentieth century and not to be nineteenth century pictoral tradition that is evident in so many of the Impressionist films. Likewise, Ballet Mechanique invigorated the idea of cinematic rhythm and created an intricate series of oppositions between internal and external rhythms.

. . . As the spread of its reputation and the response of artists and film-makers attested, Ballet Mechanique was seen as a breakthrough – an avant-garde film certainly, but one which could break out of the enclave and establish its own terms of recognition.

Source: Ian Christie, “French Avant-garde Film in the Twenties: from ‘Specificity’ to Surrealism’,” Film as Film: Formal Experiment in Film 1910-1975

Can you see Léger’s nascent modernist point of view in his set designs for L’Inhumaine? See for yourself in the image gallery below.