By Sarah Bastin

Film historian and preservationist David Shepard is the founder of Film Preservation Associates, the owner of Blackhawk Films® Collection and the producer of many Flicker Alley titles, including Masterworks of American Avant-garde Experimental Film 1920-1970, Chaplin’s Essanay Comedies, Landmarks of Early Soviet Film, Georges Méliès: First Wizard of Cinema and our entire Manufactured-On-Demand (MOD) library.

Shepard graciously agreed to talk about Five American Experimental Films of the 1950s and The Ghost That Never Returns, coming soon to MOD Blu-ray!

Let’s start with Five American Experimental Films of the 1950s. Four of these films arrived after our Masterworks of American Avant-garde collection went to press, so they could not be included. What made you decide to give these works their own release on MOD Blu-ray?

I thought they were wonderful films, and of the five, four really have not been seen in at least 35 years. We had beautiful material on all of them, so what’s not to like?

These films are completely devoid of narrative and approach film as a purely visual art.

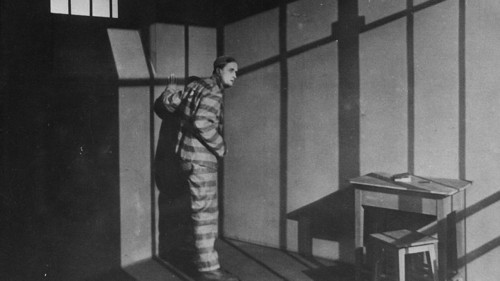

Still from Abstract in Concrete (1952). Director John Arvonio filmed lights reflecting on street puddles, creating the illusion of an oil painting.

Abstract in Concrete looks like an expressionist painting; the neon lights playing on wet concrete look like the impasto painting technique where thick layers of paint are applied to a canvas.

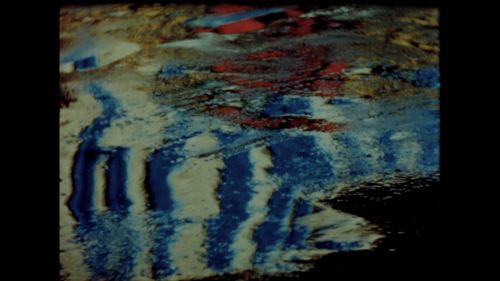

Still from N.Y., N.Y. (1957). Director Francis Thompson built special mirrors and devices into his camera to achieve his surrealist shots.

Francis Thompson’s N.Y., N.Y. has images where distorted buildings seem to hang in midair; it feels like a Salvador Dali painting.

What do you get out of this collection on an artistic level, and do you think film should be viewed more as a visual art than a dramatic one?

First of all, there was no intended thematic unity to the collection. It was simply to present some films that I thought very highly of, and each one really has to stand as an individual work because of course they’re artist’s films and were made according to the desires of the filmmakers.

As to my own preferences, film can be many things: it can be a historical document; it can be, of course, a narrative; it can be truly a work of art.

To the extent that anything unifies the films in this anthology, it’s that they’re largely pattern works. That’s an old tradition in experimental films. You can see it, for example, in the Masterworks of American Avant-garde, in the [Ralph] Steiner film Mechanical Principles (1930), which is not that radically different from Treadle and Bobbin (1954), which is 24 years later. [This technique], of course, is a very convenient way for an independent filmmaker (who’s doing things as time and money allows) to make a film, because a sewing machine isn’t going anywhere, and you can experiment, try editing, go back to it, and essentially manicure it until it has the high level of perfection that the filmmaker has in mind, which is a rare opportunity.

Still from Treadle and Bobbin (1954), starring a Singer sewing machine. The sewing machine took a pay cut to appear in the film and was reportedly always on time to set.

Now, when you’re doing a film like N.Y., N.Y., which was shot over a period of several years… Francis Thompson went out with his Kodak Ciné-Special camera and all the devices that he built to distort the image, and shot footage, and finally in the end, he used the dawn-to-dusk organizing principle, which is a familiar one in city-symphony films going all the way to the 1920s with a film like Berlin, Symphony of a Great City, which I think Flicker Alley is selling now on MOD…

That’s correct.

It becomes an organizing principle for material which he’s gathered, without really probably having the organizing principle in mind. And that would be true as well of [John] Arvonio’s film Abstract in Concrete, where obviously he went down to Midtown Manhattan in the rain and just began shooting lights and reflections in puddles and all kinds of things that could then be organized at the editing stage into a pattern that would have some graphic quality and perhaps some meaning. Pattern films, made with more-or-less control, remain I think even today one of the fallbacks of many avant-garde filmmakers.

Title shot of Francis Thompson’s N.Y., N.Y., also available on Masterworks of American Avant-garde Experimental Film 1920-1970.

The only film on this collection that we have previously published is N.Y., N.Y. Can you tell us a little bit about it and why you are including it again on this anthology?

N.Y., N.Y. is a very famous film which had not been seen very much at all since probably the 1960s. I first saw it when I was in high school, and it completely knocked me out. Francis Thompson, who made it, also made a couple of other films that I regard as among the best I’ve ever seen, but it’s impossible to see them now because they were made for multiple screens….

United Artists did distribute [N.Y., N.Y.] theatrically for a few years. It disappeared after that, and Francis Thompson kept the original edited camera film under his bed for 40 years, and nobody did anything about it.

It was Bruce Posner, our collaborator on Masterworks, who went to see Thompson on behalf of Anthology Film Archives and himself, and was able to get Thompson to give him both the film and rights; and I obtained it from him….

I really want this film to be seen. So, we used it both on Masterworks and on this anthology [Five American Experimental Films of the 1950s]. It’s the only thing on the anthology of five that is repeated from an earlier outing, but I think it’s a film that you can see 25 times and each time find new things in it. It’s a really rich, beautiful film.

Still from Analogies No. 1 (1953) by Jim Davis. No, not that Jim Davis.

If people haven’t experienced experimental film before, do you hope that they can sample it on this MOD, and if they like it, then they can pick up our larger Masterworks of American Avant-garde collection?

Oh, yes, absolutely—that’s part of my thinking. It gives people an inexpensive toe in the water…. It’s a sampler. In this particular case, they’re beautiful transfers, beautiful films. Nothing second rate about them in any way. The only reason that they came out as a separate item, as the description says, is because I got them too late to premiere on the Masterworks set.

Was it important to you that they premiere on Blu-ray? As far as we know, this is the first time four of these films—every film except for N.Y., N.Y.—are going to be on Blu-ray.

It’s the first time they’re on any form of video. They were never even on VHS or laserdisc or DVD. For these particular films, the sound is not terribly important. These are visual works, and when [the focus is on] the image, it should look as good as possible.

Let’s talk about our other MOD Blu-ray release The Ghost That Never Returns, a Soviet film from 1930. What do you think audiences will get out of this film?

First of all, I think there will be some knowledgeable people who will be curious about it because it is directed by Abram Room. Bed and Sofa, which we’re already selling as MOD, is his most famous film, and it’s an extraordinary film to come out of the Soviet Union. There’s no Revolution, there are no tractors, no collective farms, none of the kind of things that are the putative content of so many of the Soviet films of the 1920s.

Although, because Soviet filmmakers in that era were somewhat restricted as to theme, they were free on the other hand to exercise style, and that’s why there are so many great masterworks in the Soviet films of the ’20s. I mean, we haven’t put them all out by any means, but films like Potemkin and Strike and October and Storm Over Asia and Mother and The End of St. Petersburg and, of course, all those Vertov films. Bed and Sofa is right up among those as an important and celebrated work.

But, Abram Room’s other silent films aren’t known in this country, except now The Ghost That Never Returns. So, I thought that was the first good reason to put it out. And it does deliver. It’s an outstanding film. The quality of the materials is disappointing, and we wouldn’t want to mislead any buyer into thinking it’s going to sparkle like the best silent film that you could find on DVD or Blu-ray. But it’s an extremely interesting film.

First of all, it’s set in South America, which is unusual. It’s a strong narrative that really pays off. It’s very well made. And it’s a work which has been almost unknown in this country probably for 75 years. It was distributed here in the early 1930s when Soviet films were mostly handled by a company called Garrison Pictures, which put them out to workingmens clubs. [But] there was nothing deader in the American market than the silent movie after the American industry had converted to sound.

So, The Ghost That Never Returns—although it was distributed here to the extent that workingmens clubs got to see it on 16mm film—was otherwise pretty much unknown in the United States. And we obtained one of those prints from the ’30s that had never been circulated, so that it was not cut up and was clean and in good condition. But for whatever reason—and I’ve seen quite a number of important films from 1929, -30, -31 from Russia in these 16mm versions—they had a poor laboratory and just didn’t get the quality out of them that was in the 35mm originals. And it suffers from that, but that’s all it suffers from. It’s otherwise an outstanding film.

When talking pictures came in here—of course they killed the silent film deader than a doornail—yet in other countries silent film as an art continued to develop. The Ghost That Never Returns is one of those late, sophisticated silents, and that’s one of the other reasons I think that people will like it.