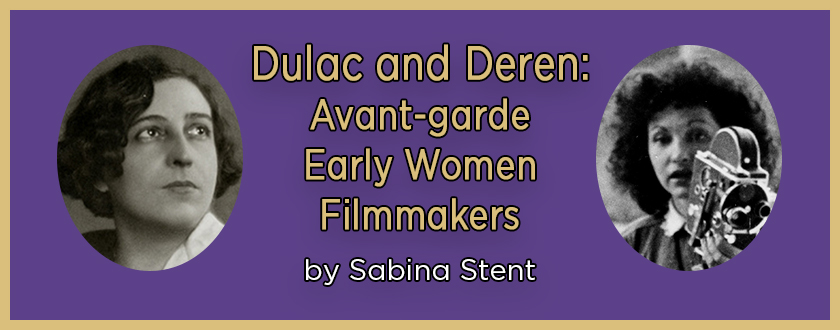

Flicker Alley is proud to present this guest essay by Dr. Sabina Stent on avant-garde directors Germaine Dulac and Maya Deren. La Cigarette and La Souriante Mme. Beudet by Dulac and Meshes of the Afternoon by Deren are featured are Early Women Filmmakers: An International Anthology, available now on Blu-ray/DVD.

Germaine Dulac

Many would not consider the avant-garde as a conducive space for women. Yet in the example of Surrealism, a movement noted for its male dominance and tendency to fetishize the feminine body, women flourished. Having found their independence through artistic creativity, they now had a platform (whether through painting, literature, or cinema) to depicts the various roles, sociological expectations, and unconscious thoughts of their gender.

While Maya Deren was the Mother of the American Avant-garde, Germaine Dulac was the Matriarch of European Cinema. With her ability to navigate and straddle multiple genres – from the dreams of Surrealism to the black and white Impressionist nightmares – her feminist work remains as fresh, relevant and noticeably pioneering as it did last century.

In 1919 Dulac made La Cigarette which was followed in 1920 by La fête espagnole (Spanish Fiesta), one of the decade’s most successful and influential films. Her central theme (not just here, but in most of her work) appears to be women’s independence. In the example of La Cigarette, the protagonist Denise is a “New Woman” who is being taught golf by her friend’s equally progressive boyfriend. Denise’s freedom threatens her older husband, who begins to feel threatened by his younger spouse’s autonomy. Mentally anguished, he becomes fixated on her apparent infidelity, and plans to commit suicide with a poisonous cigarette. Forbidden to smoke by her husband, the cigarette imbues Denise with a surprising amount of power.

La Cigarette (1919)

Dulac also exercised a woman’s command in La Souriante Madame Beudet (The Smiling Madame Beudet) (1922), a renowned piece of Impressionist filmmaking widely regarded as one the first feminist films. However, on this occasion she pushes the tone in a darker direction, to uncover a distinctly concealed side to domesticity.

Madame Beudet (Germaine Dermoz) is bored in her marriage, and prefers a night of reading at home to an evening at the theatre with her husband. She constantly laughs and jeers behind his back, an action born as much out of contempt as of pity. Most significantly, she is exasperated by his juvenile antics, especially his prank of repeatedly pointing an unloaded gun to his head and threatening suicide. After a heated argument, she decides to load the bullets into his gun…

Photomontage, overlapping, jump cuts, edits – they are all combined so we are not quite sure whether we are in a dream or witnessing a character’s lucid actions. Very often one feeds into the other to the point where they not only blur, but overlap and entwine. Dulac executes her technique so seamlessly, we are never quite sure if Madame Beudet is awake or asleep as she carries out her actions.

La Souriante Mme. Beudet (1922)

Dulac broke new territory in 1928 with La Coquille et le clergyman (The Seashell and the Clergyman), a work that preceded Salvador Dalí and Luis Buñuel’s seminal Un chien andalou as the first original Surrealist film, yet she is all too frequently dismissed in this genre. Centered on a Priest’s desire for a General’s wife, the film is filled with sexual and psychological imagery. The music is as equally disaffecting, jarring and seductive – clanging cowbells, flutes and pipes – while rooms full of smoke create the sense of disorientation, hypnotizing the audience into the dreamlike scenario of the situation. Scenes merge into each other, fade and blend, while the equally oneiric music (bells, chimes, flutes), add to the overall synesthesia and sense of hypnosis.

Women in all their various social hierarchies dominate the film, from a group of women cleaners who provocatively stick out their tongues to tease and arouse the men, to flâneuses who wander the streets of Paris and publicly exercising their independence. Women are the motivation and the essence of this film, the impetus and the cause of the Priest’s passion and torture. In his Surrealist Manifesto, André Breton repeatedly spoke of “the problem of woman.” Dulac is more than hinting at his statement.

However, the film’s production was fraught with animosity. Dulac and Antonin Artaud (who had written the film) constantly clashed over the script’s treatment. The hostile atmosphere continued after filming; Artaud claimed Dulac “ruined” the film, while the British Board of Film Classification stated, “This film is so cryptic as to be meaningless. If there is a meaning, it is doubtless objectionable.” When Un chien andalou was released the following year in a blaze of publicity and showmanship, it was heralded as “the first Surrealist film,” therefore erasing the necessity and influence of its predecessor.

Dulac’s intentions as a filmmaker was to achieve “Cinéma Pur” (or “Pure Cinema”), stripping the filmmaking back to its most natural, and untainted, form by presenting unaltered scenes of movement, vision and rhythm. This was very similar stylistically to Deren.

Maya Deren

Deren was at the forefront of artistic cinema and paved the way for independent filmmaking. Her legacy remains so relevant that in 1986, 25 years after her death, the AFI created the Maya Deren Award to recognize and honor independent filmmaking. Vehemently anti-Hollywood, and intent to maintain independence and creativity, her vision was a new model of Dulac’s “Pure Cinema.” As she once famously said, “I make my pictures for what Hollywood spends on lipstick.”

A writer, poet, lecturer, dancer, choreographer, and photographer whose work was filled with Surreal imagery, politics, and psychology, her style of cinema is humorous and playful, hinting at the movement’s ideas and politics and subverting them through a feminist lens. Encircled by creativity, and with interests including voodoo/voudou, Haiti and ethnography, she brought the female body back to its rawest and more organic form. Magic and the supernatural flood her work in an exploration of movement – both physically and mentally, consciously and unconsciously – though various interior rooms and exterior landscapes.

Meshes of the Afternoon remains Deren’s best known work, and is often bestowed with the label of “trance film.” Her collaboration with then-partner Alexander Hammid, it is frequently labelled as the first narrative avant-garde American film, where the protagonist (Deren) walks through a house to repeat the same actions. After initially falling asleep, she encounters both a shadowy figure with a mirrored face and several versions of herself (who are all attempting to harm her). She wanders and repeats the same actions, and finds numerous objets trouvres (found objects that the Surrealists believed had magical properties) in the forms of a knife and key. It’s a work of cryptic cinema that has produced multiple analyses of varying conclusions. Are the items intended to capture or free her from constraints? Is she in battle with her mind or her body? Will freedom come when she shatters the mirror? Or will she be forever trapped in her unconscious?

Meshes of the Afternoon (1943)

Deren frequently explored the concept of time: its malleability, how women are affected by time, and the effects of time on the body. Germaine Dulac and Maya Deren may have been decades apart, but their work remains a timeless feat of skill, groundbreaking techniques and innovations. They continue to be as essential to art history as to film theory. Women are often sidelined, written out or ignored in mainstream history. However, there is no denying it: avant-garde cinema belonged to women.

Sabina Stent is an independent scholar. Her Ph.D. thesis was titled Women Surrealists: Sexuality, Fetish, Femininity and Female Surrealism (University of Birmingham, UK, 2012) and she continues to research, write, and guest lecture on the subject. On May 19, 2017, she presents the lecture “Leonor Fini, Surrealist Sorceress” in London. Learn more at SabinaStent.com and follow her on Twitter @SabinaStent.

Early Women Filmmakers: An International Anthology

Now Available to Own on Blu-ray/DVD

On Sale through May 16, 2017

Sign up for our blog feed to receive instant email notifications of new blog posts!