Flicker Alley is proud to present the following essay by Robert M. Fells.

Robert M. “Bob” Fells is an independent film historian and author. An attorney and trade association executive in the Washington, D.C. area, Bob has been collecting films and related books, photos, and radio broadcasts for over 50 years. He is the official biographer of George Arliss and maintains two blogs at ArlissArchives.com and OldHollywoodinColor.com.

Film buffs love to debate who is the funniest silent film comedian of all time. Max Linder and John Bunny were among the first and their films remain delightful. Walter Kerr encouraged such discussions by devising tiers of “silent clowns” as he called them (and titled his book too). The first tier included Charles Chaplin, Buster Keaton, and Harold Lloyd—and maybe all too briefly, Harry Langdon. Yet who was best among The Best will never be settled. I have heard yardsticks used such as clocking the number and intensity of audience laughter in a Chaplin two-reeler compared to a Keaton two-reeler. I doubt that claiming that one film got more laughs than another allows us to conclude the first is superior. In fact, you may have noticed how easy theater audiences laugh at anything on the screen. But that’s a subject for another essay.

If we are willing to accept the premise that the comedy kings are Chaplin, Keaton, and Lloyd—notice that I placed them in alpha order—why can’t we take the logical next step and establish their priority? Actually, that’s been debated on many social media sites and Mr. Chaplin always seems to come out on top. OK, but then who is Number Two, and thereby hangs never-ending arguments. I have my own theory of the person Charlie himself was always looking over his shoulder to see, and I believe I have discerned the identity of Chaplin’s greatest rival. I have arrived at this conclusion not based on my flawed opinion or faulty reasoning, but by deducing the person I think kept Chaplin awake at nights and whom he feared being compared to.

When Charlie arrived at Keystone Studios in early 1914 he might have felt that Roscoe Arbuckle or Ford Sterling were the stars to beat. Both men were Mack Sennett’s mainstays and Chaplin likely studied their films to see why they were so popular. I’m not ignoring Mabel Normand but she was literally in a class by herself. What Charlie observed in 1914 is the same thing we observe when watching these films a century later: frantic activity, lots of kicks and punches, no characterizations, and a plot that might be better described as a fleeting thought. The early Chaplin Keystones such as KID AUTO RACES IN VENICE show Charlie trying to fit right in with the physical havoc. But then something wonderful happened: he started thinking.

When Charlie arrived at Keystone Studios in early 1914 he might have felt that Roscoe Arbuckle or Ford Sterling were the stars to beat. Both men were Mack Sennett’s mainstays and Chaplin likely studied their films to see why they were so popular. I’m not ignoring Mabel Normand but she was literally in a class by herself. What Charlie observed in 1914 is the same thing we observe when watching these films a century later: frantic activity, lots of kicks and punches, no characterizations, and a plot that might be better described as a fleeting thought. The early Chaplin Keystones such as KID AUTO RACES IN VENICE show Charlie trying to fit right in with the physical havoc. But then something wonderful happened: he started thinking.

With barely a dozen short films under his belt, by the spring of 1914 Chaplin is writing and directing his films and refining his Tramp character that he introduced practically from Day One in KID AUTO RACES. Seeing these films in chronological order gives us a front row seat to witness the evolution of Charlie Chaplin. Being first has both risks and advantages but Charlie could experiment with the field wide open to him. In 1914, the public had yet to hear of Harold Lloyd or Buster Keaton or Charley Chase for that matter. One man who was carefully watching the evolution of Chaplin during this time was his boss, Mack Sennett. But Sennett didn’t exactly like what he saw. The pacing of the films was slowed, apparently for no reason except to provide nuance and character development. Sennett must have worried that audiences would get bored without non-stop action, not realizing that they were getting bored because of the non-stop action.

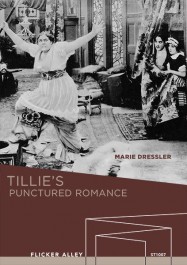

By late 1914, Charlie’s contract at Keystone was coming to an end but he learned and practiced the fundamentals of comedy filmmaking. He apparently also learned that just as you can work some comedy into essentially dramatic films, you could work a little drama into comedies. The six-reel feature, TILLIE’S PUNCTURED ROMANCE, would be the last film Chaplin ever made where he was not in full creative control. His services to Keystone expired at the end of 1914 where he had appeared in a total of 36 films, thus serving an apprenticeship that would turn into a mastercraft in 1915. Charlie had signed an incredibly lucrative contract with the Essanay Film Manufacturing Company that gave him complete creative control. He was now free to pursue ideas that he had to fight over with Sennett.

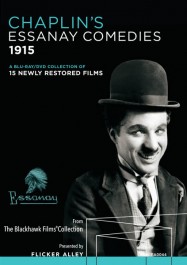

The 15 films that Charlie created at Essanay became the first true Chaplin classics and made him the most popular film star in the world. He wrote, directed, and starred in these two-reelers (IN THE PARK and BY THE SEA were one-reel exceptions) and hired beautiful Edna Purviance to play his romantic interest in each of these. Similar to viewing his Keystones, the early Essanays are a bit rough and lacked the polish Charlie would give to his later productions at the studio. Indeed, like the Keystones, it is easy to tell which films were made early in his tenure at Essanay and which came later. For example, watch THE CHAMPION that was made in the spring of 1915, then compare it to THE BANK or BURLESQUE ON ‘CARMEN’ made later in the year. The learning curve is obvious and the two latter films are much more polished than the first.

If Chaplin’s year at Keystone can be called his grammar school of cinema, then the year at Essanay was his high school. He signed a new contract with Mutual Film Corporation in 1916 where he was to make 12 two-reelers in one year. Charlie made the twelve but it took him nearly two years to do it. Edna Purviance returned as his leading lady and a number of his supporting cast from Essanay continued, especially the gigantic Eric Campbell, who was as familiar a presence as the villain as Chaplin was himself. The Mutuals continued Chaplin’s upward track as he continued to refine his comedy ideas. If his Essanays are demonstrably superior to his Keystones, I’d say there is no controversy that his Mutuals are the best of all.

Chaplin did not merely polish his craft at Mutual. He continued to experiment and take chances. For example, an early Mutual, ONE A.M., is literally a solo turn with no other actors appearing (excepting Albert Austin’s brief bit as a taxi driver at the opening). This film is inventive but after a while the viewer becomes aware that this a “trick” film to see how far Charlie can carry it without a cast. This self-conscience stylization becomes a distraction and Chaplin never repeated the experiment. But sometimes we learn more from our mistakes then we do from our successes. Mr. Chaplin was no exception.

The Mutuals show us Charlie Chaplin at the top of his game, young, energetic, newly wealthy, and the darling of the world. Of course, his peers were also watching his films and borrowed, expanded, and did riffs on his comedy. For example, Harold Lloyd’s character of Lonesome Luke was an exact opposite of Chaplin’s Tramp. Where Charlie wore baggy points, Lloyd wore tight ones—you get the idea. But if imitation is the sincerest form of flattery, then the creative comedians did not stop at copying Chaplin. They developed their own personas and their own universe. Perhaps this is what sets Lloyd and Keaton apart from, say, Billy West who was content to be a Chaplin imitator and lacked ideas of his own.

Chaplin reached a sort of creative mountaintop with the Mutual films. If I may press the point, one might say that he “plateaued” creatively at Mutual. By 1918 Chaplin signed with First National and continued making wonderful two-reelers such as THE IDLE CLASS (my favorite among the First Nationals) and THE KID, his first feature film (ignoring TILLIE’S PUNCTURED ROMANCE where he had no creative control). But it’s hardly a minority view to say that as a group the First National films offered little new artistically. Chaplin seemed to realize this too because he took longer and longer to finish each film, perhaps straining to keep them at the same level of the Mutuals. Indeed, commentators have not hesitated to find some of the First Nationals such as PAY DAY and SUNNYSIDE to be inferior to the Mutuals.

So perhaps it was no surprise that after completing his First National commitments, the Tramp would go on hiatus for two years while Chaplin busied himself with other projects. Even his partners at United Artists, formed in 1919, were left cooling their heels waiting for Chaplin to start making films for their own company. Then too, other popular comedians such as Arbuckle, Lloyd, and Keaton were leaving two-reelers by the early 1920s and would make features exclusively, typically on a two film per year schedule. Only in 1925 would the Tramp finally return to the screen in THE GOLD RUSH, which proved to be a blockbuster. Thereafter, three years would pass before a new Chaplin film was seen (THE CIRCUS), then three years again (CITY LIGHTS), then five years (MODERN TIMES). A wealthy man by then, had Chaplin lost interest in filmmaking?

Apparently not, but there are accounts by those who were there that Chaplin had become a perfectionist as though his latest project had to meet some lofty standard that no other films did. So who was Chaplin’s greatest rival that seemed to create an impossible standard? My theory is that it was not Lloyd or Keaton, or anybody else. Chaplin’s greatest rival was himself, that is, his younger self and the films he made when he was inventing the grammar of film comedy. With the Keystones, Essanays, and Mutuals still being shown theatrically—Charlie did not own the rights to them—he found that he was competing with himself.

For a limited time, SAVE 20% OFF The Mack Sennett Collection, Vol. One when you apply promo code SLAPSTICK at checkout! Promo code expires September 21, 2016 at 11:59 p.m. PST.